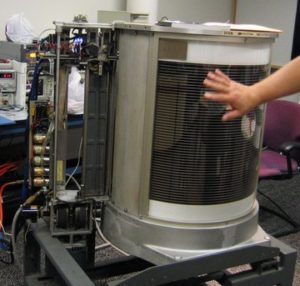

The IBM 350 Ramac storage disk at the Computer History Museum. Credit and Creative Commons License.

We’re approaching the 70th anniversary of the hard disk drive (and despite a popular misconception, hard drive sales are still going strong). Without HDDs, modern computing wouldn’t be possible, and when the IBM 350 was introduced in 1956, it jump-started a revolution in data storage.

Here are a few strange facts about the IBM RAMAC’s 350 “disk storage unit” and its extraordinary impact on computing.

1. The first commercial hard drive wasn’t available for purchase.

The IBM 350 was introduced as the central component of the IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Method of Accounting and Control) computer system. Capable of storing 3.75 megabytes of formatted data, it was a revelation — but you wouldn’t actually buy it.

At the time, computers were big mechanical systems that required frequent servicing; if you didn’t have an on-staff engineer to maintain the system, you couldn’t justify buying the entire device.

Instead, businesses could rent the hard drive along with the RAMAC system for $3200 per month (the modern equivalent of about $37,500).

2. The IBM 350 weighed more than a ton.

What set the IBM 350 apart from other storage solutions was its ability to access data randomly, without going through each bit of data sequentially. Programs and files could be accessed in any order. That’s how we use data today, but it wasn’t possible until the introduction of magnetic storage.

So, why was random data access important? For fairly boring reasons: In business accounting, transactions needed to be handled as they occurred, which necessitated a new form of data storage.

But to create that storage, IBM had to do some literal heavy lifting. The RAMAC 350 storage unit had 50 24-inch discs (platters) and weighed about a ton (1,730 pounds). A separate air compressor unit was necessary for operation; that added another 441 pounds.

3. It was almost canceled because it threatened IBM’s punch card business.

Prior to the introduction of magnetic storage devices, data was stored on paper punch cards. A computer system could “read” the holes in the card stock, which correlated to binary data.

In the mid-1950s, IBM had an effective monopoly on punch card storage. Their 12-row, 80-column punched card format was a standard — and a substantial source of profit for the company. The RAMAC 350 storage unit could hold enough data to fit about 62,500 punched cards, and access the data randomly.

That’s why the IBM Board of Directors was skeptical about the IBM 350: Hard disk drives would allow data to be written and rewritten, without requiring paper input. That was seen as bad for business, and the Board canceled the drive’s development.

Fortunately, IBM was a large company, and its San Jose laboratory continued to work on the RAMAC 350. By the time the unit was ready for market, the growing needs for data storage in business accounting had made magnetic storage inevitable, and IBM’s president gave the RAMAC 350 the official go-ahead.

Learn more about the history of data storage.

For more info on the history of hard drives — and data storage in general — read: The Rapid Growth of Storage Technologies: How Data Capacities Changed (And How They’ll Keep Changing).

If you’ve lost data from a RAMAC 350, you’re on your own. But if you’ve lost data from another hard drive, solid-state drive, RAID array, or any other device, we’re here to help. Datarecovery.com provides risk-free evaluations, and we support our services with a no data, no charge guarantee: If we’re unable to recover the files you need, you don’t pay for the attempt.

With industry-leading technology and fully equipped laboratories at every location, we provide reliable resources for hard drive recovery, ransomware recovery, and more. Call 1-800-237-4200 to speak with an expert or submit a case online.