Every week, new strains of ransomware infect computers or are spotted by security researchers while still in development. Most of them are small-scale operations that attract little attention.

Every once in a while, a new malware will make headlines based on some novel feature. The distributors of Popcorn Time, an in-dev ransomware, would decrypt a victim’s files if they infected two other victims who ended up paying.

Jigsaw used images from Saw to increase the intimidation factor and brand their otherwise nondescript malware. Philadelphia ransomware can be bought as a service and tweaked to fit an attacker’s specific needs. However, none of these have proven to be large players in the long run.

There are a handful of malicious programs that have changed the landscape of the ransomware world. Here are the four most revolutionary, game-changing ransomware strains and how they influenced their successors.

The AIDS Trojan Horse: The Advent of Ransomware

In 1989, an evolutionary biologist named Joseph Popp distributed 20,000 floppy disks to AIDS researchers around the world. The disks contained a questionnaire that Popp claimed would help doctors determine a patient’s risk of developing the AIDS virus. In reality, Popp had hidden an early form of ransomware on the disks and was using a social engineering technique to spread it.

To avoid being pinpointed as the author of the malware, Popp wrote the code so that the ransomware lay dormant until an infected computer booted up 90 times. On that 90th boot, the virus encrypted the computer’s files and displayed a ransom note.

The note instructed victims to send $189 to a PO box in Panama, a country with infamously lax business laws. Few victims made payments and British authorities quickly arrested Popp and charged him with blackmail. He avoided jail time when a judge declared Popp mentally unfit to stand trial. In the meantime, a researcher named Jim Bates created a tool to restore victims’ files by removing the virus and decrypting the files.

What it changed: Popp’s malware had four characteristics that future ransomware developers and distributors would copy: a scaremongering note, a hard-to-track payment scheme, encryption of important files (albeit rudimentary and breakable), and the use of social engineering to trick victims into installing the malware themselves.

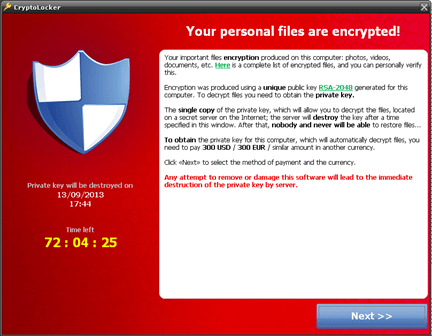

CryptoLocker: Ransomware Modernizes and Scales

In September 2013 (almost 25 years after the first ransomware incident), the modern era of ransomware began. CryptoLocker spread through the Gameover ZeuS botnet via infected email attachments.

The exact number of victims is unknown, but estimates suggest there were 500,000 people who lost data because of CryptoLocker. This sophisticated crypto-ransomware may have been too successful for its own good, as the staggering number of victims prompted international cooperation to catch the attackers. The U.S. Department of Justice, the FBI, Europol, and others collaborated for Operation Tovar, which took down the Gameover ZeuS botnet and gained access to the decryption keys.

While all victims eventually had the opportunity to decrypt their data, it took nearly a year for law enforcement and security firms to create a tool for this purpose. The CryptoLocker attack was an early indication that ransomware had the potential to massively disrupt business and prevent access to data from thousands of miles away.

What it changed: CryptoLocker showed the devastation that a large botnet could cause when it sends out millions of phishing emails infected with ransomware. The sophisticated encryption method also proved that ransomware could permanently prevent access to files when the decryption key was withheld.

Hidden Tear: Open-Source Code Makes Ransomware Easy

Utju Sen was a Turkish programmer who created a ransomware called Hidden Tear. Sen didn’t want to use the malware for financial gain, but he did want to share his creation. So, he made it freely available to download for educational purposes. Sen built several backdoors into the code so that any files encrypted by it could be decrypted.

Hackers quickly realized they could use Sen’s code for ransomware campaigns of their own. They also realized that they could tweak the code to close the backdoors. To make matters worse, some of the variants had changes to the code that made it difficult to decrypt—even if the attackers supplied the decryption key.

Variants of Hidden Tear continue showing up in new guises. In June 2017, a McAfee engineer found that nearly 30 percent of new ransomware strains were based on Hidden Tear.

What it changed: Hidden Tear provided open-source code for programmers who have minimal skills to attack computers. Even inexperienced hackers who botch the code can wreak havoc and earn money (even if they can’t successfully decrypt encrypted files).

WannaCry: With Help From the NSA, Ransomware Spreads Fast

This sophisticated attack combined ransomware with a worm that targeted a vulnerability in older Microsoft Windows operating systems. The public was shocked to learn that the U.S. National Security Agency had discovered the vulnerability and created a hacking weapon out of it (known as an exploit) rather than report it to Microsoft.

The worm aspect of WannaCry allowed it to spread laterally to other computers on the same network. One of the hardest hit organizations was Britain’s National Health Service, whose services were severely disrupted. Germany’s national railway service, a Spanish telecom giant, and French carmaker Renault were all affected by the attack as well.

The cryptoworm spread to over 150 countries over the course of 48 hours. The spread slowed when a security researcher Marcus Hutchins found a kill switch in the malware’s code. Microsoft also took the unusual step of providing a patch for their older, unsupported operating systems to prevent any further attacks using the NSA exploit.

What it changed: The attack proved how quickly a combined ransomware/worm can spread—especially on networks using unsupported operating systems. Sadly, the Petya/Nyetna attack that occurred months later successfully targeted the same vulnerability on thousands of computers that still were not patched.

What Comes Next?

Many of the tactics used by the above strains of ransomware continue to be used today. Mass phishing campaigns conducted by botnets allow attackers to cast a wide net for potential victims. As email providers get better at detecting malware in attachments, hackers change their tactics to better hide it.

To protect your home or business from ransomware attacks, you don’t need to predict the exact method that hackers will use. Rather, protect yourself from any data loss situation by regularly backing up all essential data. Having reliable backups on media disconnected from your computer can save your data from ransomware attacks and the more mundane situations that might occur.